The Reformation and Psalm-Singing

Worship was one of the key issues that led to the break with Rome we call the Reformation. The Reformation was not only about theology, but also about doxology — about the proper way of giving all glory to God. When I speak about worship here, let me clarify that I’m referring to the corporate worship of the church. This is about what happens when the church gathers together for public worship.

When it comes to the Reformation of worship in the 1500s, there are several directions we could go. A fruitful area of consideration for our day would be the singing of Psalms. This is because of the fact that so much Protestant worship today either totally ignores the Psalms, or reduces them to the occasional singing of something like “Create in Me a Clean Heart.” As in the medieval church prior to the Reformation, the Psalms have fallen on hard times.

In the early church, the Psalms were highly valued and extensively used in worship. In his dissertation, The Patristic Roots of Reformed Worship, Hughes Oliphant Old notes that Augustine indicates several times in his sermons that his church in Hippo customarily sang the Psalms. Basil the Great also spoke in a similar vein, as did John Chrysostom. Old concludes, “The early Christians sang psalms in the celebration of the Eucharist [the Lord’s Supper] and in the daily morning and evening prayers during the week. Psalms were sung at meal time as a table blessing, they were sung at work and during the quiet times of meditation at midday and evening” (258). While the Psalms were not used exclusively, they were given preference and formed the primary song material of the Church.

This pattern continued into the medieval period. For most of the Middle Ages, the Psalter was the primary material for the singing and chanting of the Church. This singing and chanting were done by the clergy and in Latin, and thus disconnected from the congregation. Yet the primary material remained the Psalter. This began to change in the early 1300s. During that time, we see the introduction of numerous Latin hymns and the primary place of the Psalter begins to slip. When there was singing or chanting of the Psalms, often this was reduced to one or two verses.

During the 1500s, God brought about the Reformation of the Church and this included changes in how God was worshipped in song. I’ll mention five specific changes.

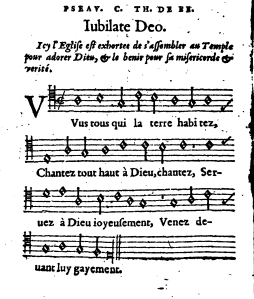

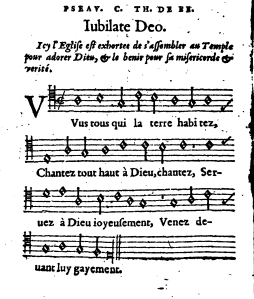

First, the Psalms were translated into the common language of the people and then set to metrical tunes. In Geneva, under Calvin’s leadership, the Psalms were translated and versified by Clement Marot and others. Musicians such as Louis Bourgeois composed the tunes — they were custom-made for each of the psalms.

Second, the Psalms were to be sung by the entire congregation. Since they were in the common language, and since they were set to tunes that were (relatively) easy to sing, this was now feasible. You did not need to be a professional musician to sing in church. That said, in places like Geneva, the Reformation did introduce an emphasis on music education. Why? Because church leaders wanted congregational singing to be as beautiful as possible to give the maximum glory to God!

Third, there was a movement back towards the priority that the early church gave to the Psalter. Says Old, “It was simply a matter of preferring to sing the hymns that had been inspired by the Holy Spirit” (259).

Fourth, the Reformation brought back the singing of all the Psalms. When the Genevan Psalter first appeared in 1542, it only contained 30 psalms. However, the goal was always to include all 150 Psalms, and by 1562 that goal had been accomplished. Not only were all the Psalms included, but the intention was to sing all of them. The 1562 Genevan Psalter included a type of schedule by which the church would sing each of the Psalms in the course of six months (see here for more details).

Finally, the Reformation reintroduced the singing of whole Psalms. While it was not always possible, the preference was to sing the entire Psalm from beginning to end. That this was the preferred practice is clear from the source mentioned above in my fourth point. This was possible because the Genevan tunes were originally composed to be sung briskly, not at a funereal pace. How and why they came to be sung otherwise is another story, but for now let’s just note that the singing of whole Psalms was the ideal which the Reformation restored.

This history is relevant at several levels. In much of evangelical worship today, it’s almost like we’re back to the worst of the medieval period. Instead of congregational singing, there are worship leaders doing the singing for the church. Oftentimes the music is so technical and the material so unfamiliar, that congregational singing in worship is virtually impossible (see Tim Challies’ reflections on this here). It’s like the Reformation and its return to congregational singing never happened!

That particular trend has been resisted in many confessionally Reformed and Presbyterian churches. Yet we still have our problems. Think of the primacy of the Psalter. In churches that practice exclusive psalmody, it’s not an issue. The Psalms are their only song material. But for those of us who see the Scriptures as commending or even commanding hymnody alongside the Psalter, the challenge is there to keep the Psalter in the highest place. Especially when we don’t understand what we’re singing, the tendency is going to be to drift towards more uninspired hymnody. Pastors especially have a calling to make sure that our churches understand the Psalter, especially in how it speaks of Christ.

Another problem faced by Reformed and Presbyterian churches is the singing of only some Psalms, and then also the singing only of partial Psalms. I am as much a part of this problem as anyone else. There are Psalms that I have never chosen for singing in public worship in my nearly 18 years of preaching. There are reasons for this (difficulty of the tune, not relevant to the sermon for the day or the occasion, etc.). That can be overcome by revisiting the idea of a psalm-singing lectionary (see here again). The other problem is easier to overcome. If a metrical Psalm only has three or four stanzas (or less), why not sing the whole thing? Especially if our accompaniment keeps the tempo brisk (as intended!), I can hardly think of a reason not to.

I love the Psalms. I love the way this inspired songbook honestly acknowledges the whole range of human emotions. We are led to praise God with explosive joy, but also to lament with flowing tears. We see Christ the Redeemer prophetically represented, but we also encounter our sin which put Christ on the cross. We’re taught to pray and give thanks. We’re taught to confess and repent. I can’t imagine worship without the Psalms. Let’s be thankful to God that the Reformation restored their rightful place in our worship!