Outward Looking Church: Current Craze or Christ’s Commission? (2)

Revised from a presentation for the Spring Office Bearers Conference held March 22, 2014 in Burlington, ON. See here for part 1.

How Do Our Confessions Answer?

Since I phrased my thesis in terms of the confessions, it makes sense to start there. There is a lot that could be said. Appeal could be made to Lord’s Day 12 of the Catechism and how it speaks of the three-fold office of Christians. As prophets we are to confess the name of Christ. Who are we to confess the name of Christ to? This obviously has an outward looking orientation. We could go on and think of Lord’s Day 32 and how winning our neighbours for Christ by our godly walk of life is part of the reason we must do good works. There again at least part of the perspective is looking outward. Or we could spend some time on Lord’s Day 48, dealing with the second petition of the Lord’s Prayer, “Your kingdom come.” We confess that this includes asking our heavenly Father to “preserve and increase” his church. The word “increase” there refers to numerical increase and that implies a certain orientation among those who pray along the lines of this petition.

We could move on from the Catechism to the Canons of Dort and the same perspective is in evidence there. It comes in connection with the doctrine of election. There are those who say that election knocks the motivation out of outreach. Maybe you’ve heard Reformed churches mockingly referred to as “the frozen chosen.” But that can only be true if we don’t take our own confession seriously. We believe and confess that God uses his church and her witness to draw in the elect. Election becomes evident (or comes to expression in history) through evangelism. Article 5 of chapter 2 of the Canons of Dort is clear enough on this point:

The promise of the gospel is that whoever believes in Christ crucified shall not perish but have eternal life. This promise ought to be announced and proclaimed universally and without discrimination to all peoples and to all men, to whom God in his good pleasure sends the gospel, together with the command to repent and believe.

Our confession says that we have a gospel promise which we are obligated to announce universally, to all peoples, all men. The language is undeniably clear. So also if we take the Canons of Dort seriously, they should produce an outward looking orientation in the church.

Indeed, we could spend a lot of time on what the Canons and Catechism have to say about this. But I want to focus our attention on the Belgic Confession this morning. Let me first explain the rationale for doing that. The period of about 1950 to 1990 was one of widespread deconfessionalization in the Christian Reformed Church. For many CRC members (but by no means all), the confessions became museum artifacts, pieces of CRC history and heritage, rather than a living expression of the biblical faith of the church. In that 40 year period, many claimed that the CRC had basically become a Dutch ghetto. The perception was that the church was turned in on itself, too often only inward looking. Discussions took place at various levels and in various venues about why this was. Blame was often assigned to the Three Forms of Unity and especially the Belgic Confession. One CRC seminary professor (Robert Recker) wrote that with the Belgic Confession we’re faced with a church “talking with itself rather than a church before the world.” Influential figures in the CRC agreed with Recker. So, in other words, if you want to know why the CRC became a Dutch ghetto turned in on itself, look no further than the Belgic Confession. Then the solution also begins to suggest itself: we can hold on to the Confession as a museum artifact, something that shows something of our history and where we came from, but for today we need a new confession which will really help us be an outward looking church. That partly accounts for the development of the “Contemporary Testimony: Our World Belongs to God.” This new confession in the CRC was adopted in 1986 and its history is rooted in dissatisfaction with the Three Forms of Unity on certain points. That included a perception that the Belgic Confession is an exercise in ecclesiastical navel-gazing. That historical episode puts the question squarely before us this morning: what orientation does the Confession provide for the church?

When we think of the Belgic Confession today, we typically think of a section at the back of our Book of Praise. This is true of all our confessions. For us, they’re embedded in a rather large book. However, around the world, in different places, these confessions are being printed separately in convenient, cost-effective formats. For example, there is the Heidelberg Catechism in Spanish produced by CLIR in Costa Rica. There is also the Belgic Confession in Russian, produced by the Evangelical Reformed Church in Ukraine. Both are in a convenient and cost-effective format so that believers can share them with others. There’s an outward looking, evangelistic intention here. They didn’t make these booklets for church members, but so that church members could share their faith with outsiders. That fits precisely with the history and original intentions of these documents, especially the Belgic Confession.

When the Belgic Confession was first published in 1561, it didn’t appear as part of a Book of Praise. It was published as a booklet in a convenient, cost-effective format. It was designed for mass distribution, not just amongst Reformed believers, but also with their friends, family, and neighbours. We know of two printings of the Confession in 1561, from two different Huguenot cities in France, Rouen and Lyons. Only one copy remains of each of those printings. We might ask why. We don’t know how many copies were involved in those first printings – it’s impossible to tell. We do know that the printing from Rouen included at least 200 copies. We know that because there is a report from the Spanish authorities saying that they found some 200 copies in the library of Guido de Bres. The Spanish authorities burned those. But other copies were circulating; we just have no idea of how many. We do know they were printed cheaply and quickly. There are a couple of possibilities to explain why we only have one copy from each of the two printings in 1561. One would be that the Spanish destroyed most of them. Another might be that they were so widely used and distributed that they fell apart and didn’t fare well over the following decades and centuries. It could be a combination of both and maybe there are other factors besides. What is clear is that, from the beginning, it was designed as a document with an outward orientation. The format speaks to that.

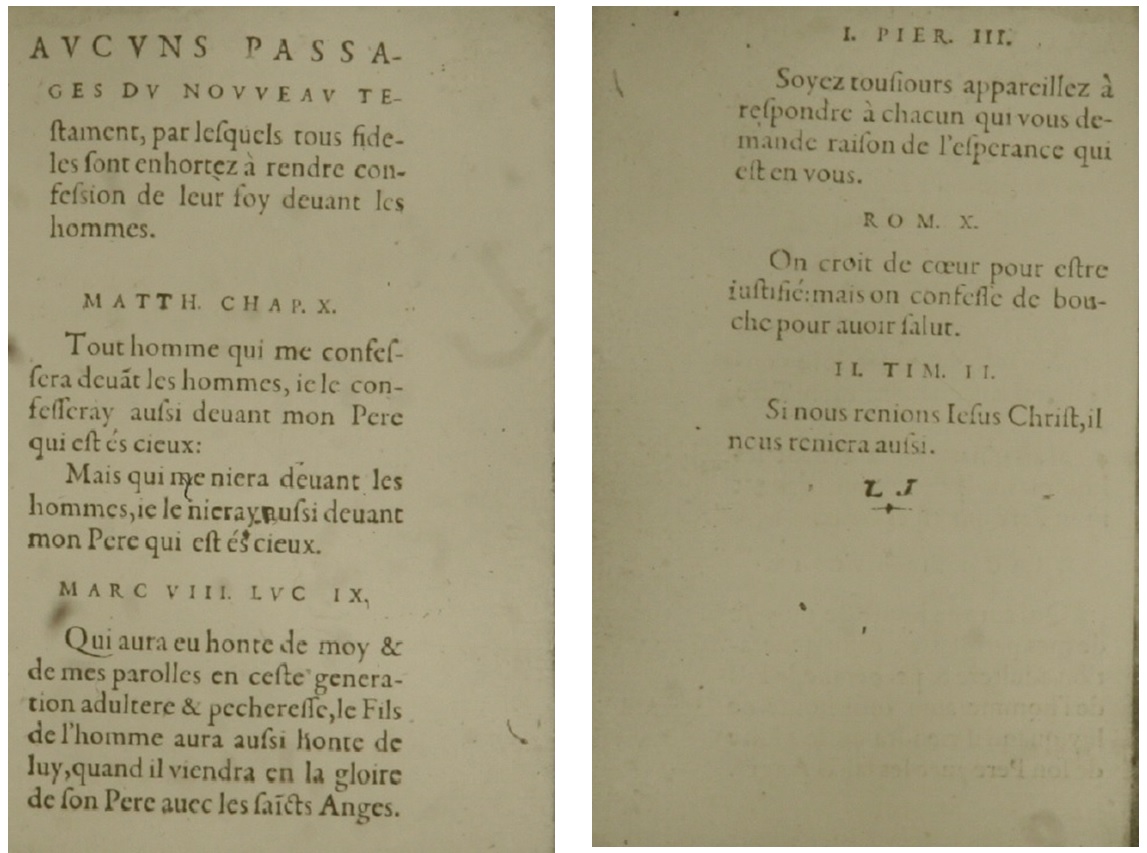

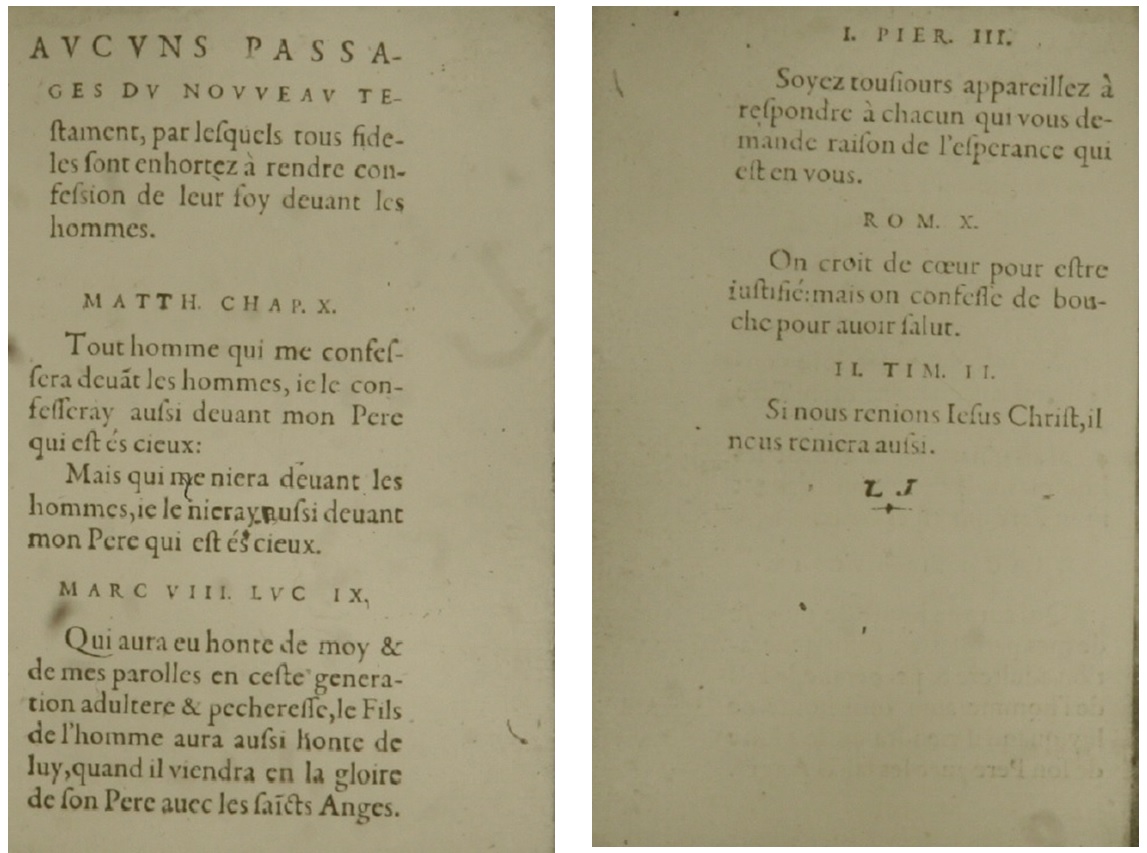

Early printings of the Belgic Confession included these two pages of Scripture passages encouraging believers to profess their faith before men.This is confirmed when we look closer at the Confession as it first came off the press. On two of the first pages of the booklet, we find a collection of Scripture passages. Over these passages were these words, “Some passages of the New Testament in which the faithful are exhorted to render confession of their faith before men.” Then followed Scripture passages: Matthew 10:32-33, Mark 8:38, Luke 9:26, 1 Peter 3:15, Romans 10:10, and 2 Timothy 2:12b. Each of these passages has an outward perspective. The point being made is that confession of faith is inherently an outward action. We confess our faith “before men,” to the world.

Oftentimes when we think of the Belgic Confession, we think of it merely as an effort to gain tolerance for the Reformed faith. The Reformed Churches in the Low Countries were persecuted by the Spanish led by Philip II, and they wanted to reassure the authorities that they were not rebellious. Instead, they were simply God-fearing people who believed what the Bible teaches. In this understanding, the Confession is simply a defense. But this understanding doesn’t do full justice to the original intent of the Confession. It was not simply to gain tolerance that the Confession was written, it was also to win converts. There was an acute self-awareness that the Reformed churches existed in the midst of unbelief and their confession was addressed to that lost world in darkness. Throughout the Confession, you find the words “we believe,” and those very words signify that there is a body of believers confessing together, confessing together to a pagan world in need of the gospel. Whenever you see a believing “we” in the Confession, you should also think of the lost “them.”

Based on these general considerations, P. Y. DeJong was exactly right when he wrote a commentary on the Belgic Confession and entitled it The Church’s Witness to the World. Earlier I mentioned the deconfessionalizing of the CRC, but you may remember that I was careful not to paint everyone in the CRC black. In that forty year period, there were men like P. Y. DeJong who stoutly resisted the deconfessionalization of the church. They argued that the Confessions were misunderstood and undervalued. Later, men like P. Y. DeJong would become founding fathers of the United Reformed Churches. Having been through a struggle in the CRC, they maintained that the Confessions, when they’re rightly understood, do not produce ecclesiastical scoliosis, a dysfunction where the church is curved in on itself.

But that’s about the broad nature and historical intent of the Confession, what about the actual content of the Belgic Confession? Does that say anything to the question before us this morning? Since we’re speaking about the church, let’s just focus on the ecclesiological articles of the Confession, articles 27-32.

Click here to continue reading part 3…

Bibliographical note: the quote from Robert Recker comes from his article, “An Analysis of the Belgic Confession As To Its Mission Focus,” Calvin Theological Journal 7.2 (November 1972): 179.