Ten Things I Learned from Reformed Scholasticism (2)

In the first part (see here), I began to make the case that Reformed scholasticism should not be dismissed out of hand. In recent years, there has been a renewed appreciation for this method and the theology which it produced. Last time, I mentioned five things where I’ve personally appreciated Reformed scholasticism:

- The Best Theology Begins with Sound Exegesis

- History Matters

- System Matters

- Asking Good Questions

- Using Precise Definitions

Today I’ll conclude with the last five things:

6. Making Distinctions

Distinguishing between different doctrines and their elements is a key marker of faithful theology. Scripture teaches us to distinguish. Moreover, the Christian Church has long recognized that he who would teach well must distinguish well. Reformed scholasticism excelled at the science of theological distinctions. Reformed scholastic theologians made good distinctions at the broadest levels. For example, Ursinus wrote in his commentary on the Heidelberg Catechism, “The doctrine of the church consists of two parts: the Law, and the Gospel; in which we have comprehended the sum and substance of the sacred Scriptures.” But they also made far finer distinctions. Benedict Pictet, for instance, wrote about the ways in which ought to think of God’s love. God’s love can be distinguished into the love amongst the persons of the Trinity (ad intra), and then his love towards creatures (ad extra). With regard to his love for his creatures, that is further distinguished: “1) God’s universal love for all things, 2) God’s love for all human beings, both elect and reprobate, and 3) God’s special love for his people.” (Mark Jones, Antinomianism, 83). Backed up by scriptural teaching, such distinctions can be quite useful for clear and unmuddled theology.

7. The Value of Logic and Analytical Rigour

Good theologians use logic to advance the truth claims of God’s Word. Our Reformed confessions do the same. However, we find this tool used most effectively by Reformed scholastics. A classic example is found with John Owen’s argument regarding the intent of Christ’s atonement. Using a powerful syllogism informed by biblical exegesis, Owen made an airtight case for definite atonement, i.e. the biblical position that Christ died only for the elect. Closely related to the use of logic is rigorous analysis. Reformed scholastics understood how to get at every angle of a particular topic. In his Syntagma, Amandus Polanus illustrated this when he discussed the doctrine of creation. Using the biblical data, he discussed the efficient, material and formal causes of creation, as well as the purpose and effects of creation. At the end of the discussion, you get the impression that every conceivable aspect has been covered thoroughly.

8. The Need for Polemical Engagement

As in our day, Reformed scholastics encountered challenges to the faith. Roman Catholics, Anabaptists, Socinians, Arminians (Remonstrants), and others needed to be addressed. It was not enough simply to make positive statements of the faith – errors also needed to be soundly addressed. Therefore, in most scholastic works, you will find polemical engagement to varying degrees. Many works from this period are exclusively devoted to polemics. For instance, Samuel Maresius took up his pen against Isaac La Peyrère and his arguments for pre-Adamites. Francis Turretin’s Institutes of Elenctic Theology was written with the idea that theology is best learned in the context of polemics – “Elenctic” in the title is derived from a Greek word which means “reprove or correct.” The Reformed scholastics were not afraid to not only defend the faith, but also go on the offensive for it. Many in our tender age might learn something from them!

9. Room for Theological Diversity (Within Confessional Bounds)

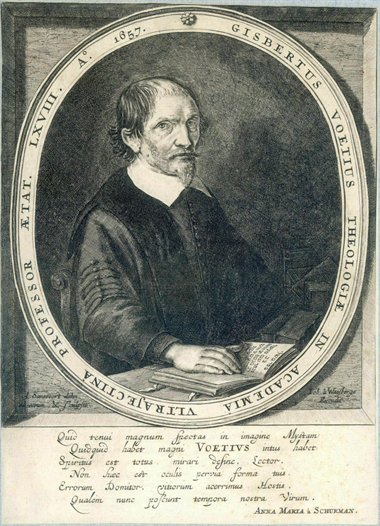

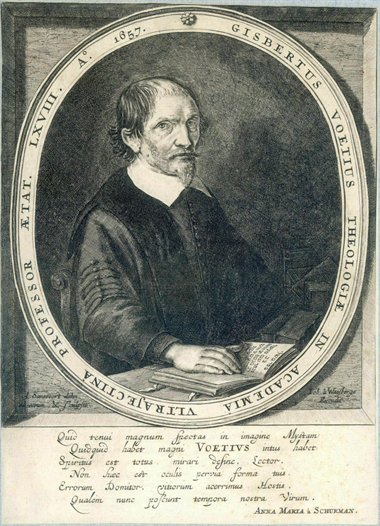

No one should have the impression that Reformed scholasticism was a monolithic movement. Yes, it may be fairly argued that there were many key doctrines on which there was a broad consensus. That consensus was defined primarily by the Reformed confessions. However, within those bounds, one can certainly find a significant amount of diversity. For example, there is the question of whether every individual believer has a guardian angel. This question is not addressed in the Three Forms of Unity. A Reformed scholastic like Gisbertus Voetius followed the lead of John Calvin and others in regarding guardian angels as, at best, uncertain. However, Voetius also mentioned that other Reformed scholastic theologians such as Zanchius, Alsted, and Chamier affirmed the ancient position on guardian angels. Can both views co-exist amongst Reformed theologians? Why not?

10. There is a Time and Place for Scholarship

The best Reformed scholastics understood one of the most important distinctions: between the pulpit and the lectern, or between the book written for the average church-goer and the book written for theology students or fellow theologians. Put more technically, they knew the difference between popular and academic. To be sure, not all Reformed scholastics did understand or employ this distinction, but the best did. Consider Gisbertus Voetius again. He was one of the most accomplished of the Reformed scholastics. His academic writings reflect his great learning, breadth of study, and scholarly abilities. Yet, this same Voetius wrote a warmly pastoral book entitled (in the English translation) Spiritual Desertion. Before serving as a theology professor, Voetius had been a pastor and he understood that there was a time and place for the scholastic method. The pulpit was not that place and neither was a book written in Dutch for ordinary church members. To communicate effectively at the level of the regular person while at the same time being able to theologize with the best theologians – this is something that most Reformed scholastics strived to attain. It’s something to aim for today as well.