Happy 450th Birthday to the Belgic Confession!

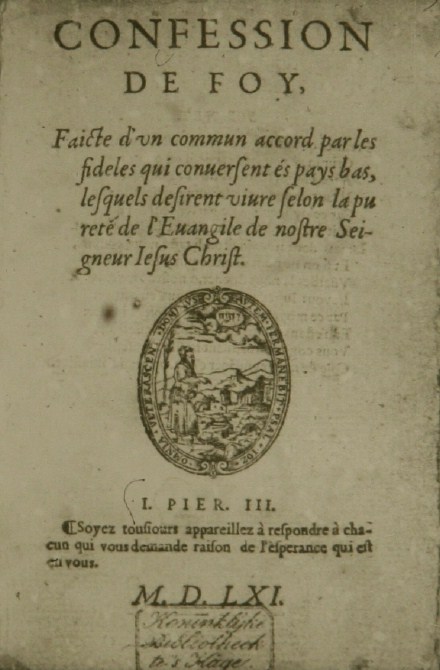

This year marks 450 years since the Belgic Confession was written by Guido (or Guy) de Bres. The Confession made its appearance late in 1561, famously being tossed over the castle walls at Tournai (or Doornik, as the Dutch call it). However, it is quite likely that the Confession was written already early that year. In his authoritative book on the Confession, Dr. N. H. Gootjes suggests that it may been written already in February of 1561.

Gootjes also believes that the Confession had been adopted by the Reformed churches in the area we know as Belgium even before it was printed. This is why the Confession uses the first person plural throughout, “We believe…” At subsequent synods, the authority of the Confession was confirmed and the text of the Confession was fine-tuned. This process continued up to the Synod of Dort and beyond. Today the Confession continues to be a living document and so is periodically fine-tuned in some of its details by churches that hold it. One of the classic examples is the original Confession’s assertion that Paul was the author of Hebrews. That assertion has been removed from the Canadian Reformed edition.

Following its publication, the Belgic Confession became widely accepted. It went through numerous printings and its first translation was into Dutch already in 1562. Within a century it had been translated into German, Latin, Greek, English, and Spanish. It quickly became one of the most widely held and respected Reformation confessions.

But why? That’s a question not often asked. We sometimes take this confessional document for granted. Did you know there were many confessions and catechisms produced during the sixteenth century? I’m not speaking of four or five or maybe ten. We’re talking about dozens. Dutch scholar William Heijting produced two substantial volumes containing confessions just from the Reformation in the Netherlands. So why did the Belgic Confession rise to the top and endure while all these others have mostly been forgotten? There are several factors.

First, as mentioned a moment ago, the Confession was accepted early on as the statement of faith of the Reformed churches in the Low Countries. It bore ecclesiastical authority from the start. It was and still is the defining confession of the Reformed churches of that region and churches that trace their lineage there. By “defining confession,” I mean that this is the starting point for what we together believe. The Heidelberg Catechism is primarily a teaching document, while the Canons of Dort are a sort of commentary on some points from the Confession and Catechism that were drawn into question by the Arminians. The Confession, on the other hand, defines what we believe corporately. It was never written as the personal confession of Guido de Bres — it always had a corporate character. It always represented the voice of the church.

Next, the Confession has been recognized as a faithful and well-worded summary of the essential teachings of the Bible. It was developed with an eye to previous confessional writings produced by such Reformed pioneers as John Calvin and Theodore Beza. It’s also firmly grounded in the biblical teachings of the early church. Quotes and allusions from the church fathers are to be found everywhere. In other words, the Reformed churches were not sucking this out of their thumbs. There was a deep respect for the tradition that respected the Bible. So the Belgic Confession has long been recognized as a clear, concise, and reliable guide to biblical truth.

Finally, the Confession has also endured because of its roots in the persecuted church. Those roots make it unique. It is the only one of the Three Forms of Unity forged in the fires of persecution and in the shadows of martyrdom. None of the authors of the Heidelberg Catechism died for their faith. Neither did any of the authors of the Canons of Dort. But on May 31, 1567, Guido de Bres was hung for “the cause of the Son of God” (as he was accustomed to say). As far as I’ve been able to determine, the Belgic Confession is the only officially adopted Reformed confession written by a martyr. Other Reformed martyrs did write confessions — there was the Guanabara Confession, written by four Reformed martyrs in Brazil in the sixteenth century — but none of those confessions were officially adopted by any church. This makes the Belgic Confession a unique document in our confessional library. It has brought Reformed believers close to the suffering church of the past. It brings us today also to the suffering church that endures crosses and trials for the sake of Christ. This too has contributed to its endurance.

The Belgic Confession is 450 years old! It has served us well, but only insofar as we have paid attention to it. The Catechism is heard each and every Sunday. But sometimes the Confession gathers dust. In his book Credo, Jaroslav Pelikan compares confessions to CDs. When CDs are stored they are inert and static. They can be handed down from parents to children without ever being used or heard. They suddenly become dynamic when placed in a CD player and the sounds of beautiful music issue forth from the speakers. Confessions only have value as they are “played,” as they are engaged and as their voice is heard through the coming generations. The 450th birthday of the Belgic Confession presents a great opportunity to “play it again.”