Reformation Confessions and Evangelism

We’re continuing to celebrate what God did in the Reformation starting 500 years ago. For today, I’m sharing the notes from a talk I did in Brazil back in August.

*************************

Introduction

One of the most important contributions of the Reformation was its production of confessions and catechisms. Only a few of them are still well-known today. For example, Reformed churches continue to use the Heidelberg Catechism written in 1563. They also continue to use the Belgic Confession written in 1561. What many people do not know is that there were numerous confessions and catechisms produced during the time of the Reformation. If we only look at the Netherlands, there were at least 18 Reformed confessions and catechism produced between 1530 and 1580.[1] James Dennison has produced a four volume set of Reformed confessions from the 16th and 17th centuries.[2] Volume One covers 1523 to 1552. It contains 33 confessions and catechisms translated into English. These come from all over Europe: Switzerland, Germany, Spain, England, the Netherlands, Bohemia and more. Moreover, this is not even close to a complete collection. The number of Reformed confessions is simply amazing.

Why did the Reformation produce so many confessions? After all, was not the Reformation all about Sola Scriptura, the Bible alone? They said they believed in the Bible alone. Yet they had all these manmade documents for their churches. How could they fit those things together? The answer is simple. They believed that their confessions were just faithful summaries of biblical teaching. Their confessions and catechisms never replaced the Bible or stood over the Bible. They were guides to the important teachings of the Bible.

The Reformation churches saw that confessions and catechisms were helpful. They were helpful as statements of faith. When someone wanted to know what their church believed, they could turn to the confession of the church. They were helpful as teaching tools. When someone was going to be brought into the church, the confessions were a pedagogical tool for teaching the important doctrines of Christianity. When young people were being discipled in the church, they would be taught with the help of confessions and catechisms. They were also helpful as something to bind the church together in doctrinal unity. These documents contained the faith that the church agreed upon together as the basis for fellowship.

In some instances, Reformation confessions were also regarded as evangelistic tracts. This is certainly true for the Belgic Confession.[3] It was addressed to a Roman Catholic world lost in darkness. It was an effort to win Roman Catholics with the gospel. The Belgic Confession was originally written in French, not in Latin. It was written in the language of regular people in order to win the regular people. It was also originally written in the format of a tract. It was printed in a small convenient format which would fit in your pocket. It was meant to be printed cheaply and in great quantities so that it could be widely shared. And it was.

In what follows, I want to look at some of these Reformation confessions and what they have to say about the evangelistic calling of the church. I’m going to mention the Belgic Confession and the Heidelberg Catechism, of course. I’m also going to be discussing some of the confessions and catechisms that are not as well known. I should say that I will not be discussing the Westminster Confession or Catechisms. These were written in the post-Reformation period in the 1600s. Our focus is going to be on the Reformation in the 1500s, particularly on the non-Lutheran side of the Reformation.

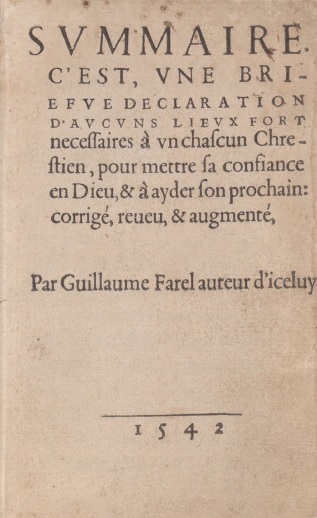

William Farel’s Summary and Brief Declaration

One of the earliest Reformers was William Farel. Farel is most remembered for the role he played in getting John Calvin to stay in Geneva in 1536. Calvin was just passing through on his way somewhere else. With fire in his eyes, Farel told him that if he would not stay in Geneva, Calvin would be cursed by God. However, there is far more to Farel than this one incident in his life. He became a Protestant in France already in 1520. He was known as a powerful and passionate preacher of the gospel. Farel also had a strong sense of the missionary calling of the church. In 1529, he was preaching in the Swiss town of Aigle. While there he drafted up one of the first Reformed confessions, his Summary and Brief Declaration.[4] This confession was a personal effort and it doesn’t appear to have been ever officially adopted by any church.

In his introduction to the Summary, Farel speaks about his purpose in this confession. He says that he was writing “for the well-being, profit, and salvation of each one.” He expressed his desire “that the whole world give honor and glory to God alone.” Finally, in the introduction he prayed that God would shine the light of his salvation in Jesus Christ “to such a degree that those from all parts of the world may come to worship our Father…” This confession had a missionary purpose behind it.

Chapter 16 of Farel’s Summary is about the doctrine of the church. The most important calling of the church is to preach the gospel. The true church of Christ must preach the gospel not only to those of a high social status, but also to the simple. Like Paul says in 1 Cor. 9:16, we will be cursed if don’t preach the gospel. And if we don’t bring the good news to the lost and wayward, Farel uses Ezekiel 3 and 33 to remind us that we will be accountable for the loss of their souls.

In chapter 17 he develops this a little bit further when he writes about the keys of the kingdom of heaven. These keys do not come from human beings, but from God. Specifically, Farel says that the Holy Spirit helps us to understand the Bible, but also sends us out to preach the gospel. Here Farel refers directly the Great Commission as found in Matthew 28, Mark 16, and John 20. Farel understood that the Great Commission to bring the gospel to the world is still a commission for the church today.

Chapter 35 is about the Power of Pastors and here too we see a missionary and evangelistic emphasis coming through. Listen to what Farel writes: “When the true pastors evangelize purely, ‘God speaks in them’ (Matt. 10:19-20) by such a great power that believers have eternal life, and unbelievers are confounded. And never will the messenger of God be overcome.” The greatest portion of chapter 35 is a prayer to God – quite unusual for a confession. Farel prays about how the Word of God has been kept out of the hands of the people for so long. He then says,

Must your holy gospel be so lowly revered so little that it is neither spoken, nor regarded, nor read? Why have you commanded that it is to be preached throughout all the world to every creature” (Mark 16:15) so that every creature may hear it and know it, if it is not permissible for each one to read it?

Notice again how he refers to the Great Commission in Mark 16. He believes it is God’s command for the church of all ages. Let me give just one more quote from chapter 35. Here again, Farel is praying:

Rise up, Lord, show that it is your pleasure that your Son be honoured, that the ordinances of his kingdom be publicized, known, and kept by everyone. And that everyone know you through your Son “from the greatest to the smallest” (Jer. 31:34). Make the trumpet of the holy gospel be heard to the ends and tip of the world. Give strength to the true evangelizers, destroy all sowers of error, that all the earth may serve, call upon, honor and worship you.

Another form of this prayer is found at the very end of Farel’s Summary. From this confession dated 1529, it is readily apparent that this Reformer had a heart for the lost and an eye for the calling of the church to bring the gospel to the lost, not only nearby, but also “to the ends and tip of the world.”

Calvin’s Catechism (1537)

Moving on to another Reformation confession, we look at something written by John Calvin. Calvin is well-known for his book, the Institutes of the Christian Religion. Calvin published the first edition of his Institutes in March of 1536. He arrived in Geneva later that year, in August of 1536. The Institutes were then quite a bit smaller than the final edition published in 1559. While the book was meant for theological training, it was not suitable for teaching children or the less educated. Consequently, one of the first things that Calvin did in Geneva was to summarize the Institutes into the form of a catechism. This was Calvin’s first catechism and it was published in French in 1537 and in Latin in 1538.[5] This catechism would have been used for teaching in the Reformed church at Geneva.

The 1537/38 Catechism is not written with questions and answers, but with articles or paragraphs. It’s still called a Catechism because it was used for teaching, and also because it contained the three essential parts of Christian teaching: the Law of God, the Apostles’ Creed, and the Lord’s Prayer. Historically, having those three parts is what defines a catechism, not having questions and answers.

Like his friend William Farel, Calvin too had a missionary heart and it shows in this first catechism. It’s especially evident when he deals with the second petition of the Lord’s Prayer, “Your kingdom come.” What was Christ teaching his people to pray for? Calvin writes, “We pray…that God’s reign may come, that is to say, that the Lord may from day to day multiply the number of his faithful believers who celebrate his glory in all works…” We are praying for the success of the gospel. Calvin adds, “Similarly, we ask that from day to day he may through new growths spread his light and enlighten his truth, so that Satan and his lies and the darkness of his reign may be dissipated and abolished.” According to Calvin, the second petition of the Lord’s Prayer has to do with evangelism.

Calvin’s Catechism (1541) and the Large Emden Catechism

In 1541 Calvin wrote a new catechism for the church in Geneva.[6] This time, however, he didn’t use paragraphs or articles. Instead, he tried the question and answer format. This catechism was large — it contained 373 questions and answers. But again, as before, it covered the Ten Commandments, the Apostles’ Creed, and the Lord’s Prayer. Just as with the earlier Catechism, Calvin links the second petition of the Lord’s Prayer to evangelism and the growth of the church. Christ was teaching us to pray that “day by day the Lord may increase the numbers of the faithful…” Note how he speaks of an increase in numbers. In the next question and answer he says something similar. The question asks, “Is that not taking place today?” The answer, “Yes, indeed – in part, but we pray that it may continually increase and advance…”

This understanding of the second petition was common amongst Reformation catechisms. I can mention two other examples. The Polish Reformer John à Lasco wrote the Large Emden Catechism in 1546.[7] This catechism too speaks of asking God to “sanctify, increase, strengthen and preserve in the unity of the faith, the gathering of the faithful…” The Heidelberg Catechism of 1563 speaks in a similar way, “Preserve and increase your church.” The word that was used in the original German for “increase” means multiply numerically. There was a consensus amongst Reformed churches that the second petition of the Lord’s Prayer involves Christians praying for God to grow his church through evangelism and mission. Just in passing you should note that this understanding is found in the Westminster Shorter and Larger Catechisms later on too.

The First and Second Helvetic Confessions

The First Helvetic Confession was published in Basel, Switzerland in 1536. There were several authors, but the most well-known of them was Heinrich Bullinger. The First Helvetic Confession was written to unite Reformed believers in Switzerland, but it was also hoped that this document could be instrumental in bringing unity with the Lutherans in Germany.

The First Helvetic Confession was therefore sent to Martin Luther for his review. It was hoped that he would approve of it and that would lay the foundation for closer relations with the Lutherans. Along with the Confession came a declaration or introduction written for the Lutherans by Heinrich Bullinger.[8] That introduction speaks of the evangelistic calling of the church. Bullinger wrote the following:

Although the Lord has expressly said, “No one can come to me unless the Father who sent me draws him” (John 6:44), yet it was his will that the gospel of the kingdom should be preached to all nations and that bishops should discharge this duty of the ministry, with great care and diligence, and with special watchfulness, and be instant in season and out of season, and by all means, that they might gain as many as possible unto Christ. For therefore, when he was ready to depart hence into heaven in his body, he said to his disciples, “Go into all the world and proclaim the gospel to the whole creation” (Mark 16:15). [9]

I really do not understand how any serious scholar can say that the Reformation churches didn’t believe in the abiding relevance of the Great Commission. We see it here again. Bullinger and the church at Basel believed that the gospel was to be preached to all nations by the church today. And it’s also noteworthy that Luther did review this confession and did approve of it – he had some reluctance but only about some of the wording in the articles regarding the Lord’s Supper.[10]

Since there was a First Helvetic Confession, there must also be a Second. And perhaps you’re wondering what that says about evangelism. The Second Helvetic Confession was written by Heinrich Bullinger and appeared in 1566.[11] The first chapter of the Second Helvetic Confession is the most well-known part of this document. It’s about preaching. Bullinger famously said that “the preaching of the Word of God is the Word of God.” What he meant was that when the Scriptures are faithfully proclaimed, God is speaking to us through such preaching. Bullinger goes on in that first chapter to point out what Scripture says about inward illumination. The Holy Spirit has to bring light to a dark heart before there will be faith. But, he says, that does not eliminate the need for preaching. Bullinger writes, “For he that illuminates inwardly by giving men the Holy Spirit, the same one, by way of commandment, said unto his disciples, ‘Go into all the world, and preach the gospel to the whole creation’ (Mark 16:15).” So the gospel needs to be preached, and not only in the church, but “to the whole creation.” Again we ought to note the abiding relevance of the Great Commission for the Church.

Many Reformation confessions spoke about the marks of a true church. Three marks are often mentioned: faithful preaching of the gospel, the faithful administration of the sacraments, and the faithful exercise of church discipline. One of the confessions that mentions these three marks is the Scottish Confession of Faith of 1560.[12] Six men with the first name John were responsible for writing it, the most famous of these Johns was John Knox. The Scottish Confession of Faith says in article 18 that the first mark of a faithful church is “the true preaching of the Word of God.” Now you might be tempted to think that this is referring only to preaching done within the church, and not missionary or evangelistic preaching. However, there is a proof-text for this statement in the original Scottish Confession. The proof text is Matthew 28:19-20 – the Great Commission.

The Belgic Confession and the Heidelberg Catechism

We find something similar with the Belgic Confession of 1561. This was written by Guido de Brès as the official confession of the Reformed churches in the Netherlands. Article 29 deals with the marks of the true and false church. Just like with the Scottish Confession, the first mark of a true church is that she practices the pure preaching of the gospel. In the first editions of the Belgic Confession, one of the proof-texts for that teaching was again, Matthew 28:18-20. The Reformed Churches were not just thinking of preaching within an instituted church in a worship service. They were also thinking of Christ’s continuing call for the church to preach the gospel to the nations.

That brings us back to the Heidelberg Catechism to finish off. I’ve already mentioned it a couple of times. The Heidelberg Catechism is the most well-known of all the Reformation catechisms – and for good reason. It was commissioned by a godly prince named Elector Frederick of the Palatinate. It was first published in 1563. It was mainly written by Zacharias Ursinus, a professor of theology in Heidelberg. He was assisted by Caspar Olevianus, a pastor in Heidelberg and others as well. The Heidelberg Catechism is loved all over the world for its warm and personal presentation of the faith of the Bible. It also deserves to be known for the way it speaks of our calling towards those who are lost. I’ve already mentioned what it says about the second petition of the Lord’s Prayer – we pray for the increase of Christ’s church. But there are other places where the Catechism speaks about evangelism, about our calling to be God’s instruments in increasing his church.

In Lord’s Day 12, the Heidelberg Catechism speaks about the three-fold office of Christ. Other Reformed catechisms do that as well, including the Westminster Shorter and Larger Catechisms. It’s common to confess that Christ is prophet, priest, and king. However, it is rare to confess that Christians share in Christ’s three-fold anointing and office. In fact, I have not been able to find any other Reformed Catechism which says that besides the Heidelberg Catechism.[13] The Heidelberg Catechism asks in QA 32, “Why are you called a Christian?” Answer: “Because I am a member of Christ by faith and thus share in his anointing…” Christ was anointed with the Holy Spirit to be a prophet, priest, and king, and so have Christians. We have the same Holy Spirit living in us giving us the same calling as our head Jesus Christ. As part of that, I may “as prophet confess his name…” This is a calling to speak to everyone we can about the Saviour. A prophet must speak. A silent prophet is unimaginable — a silent prophet is an oxymoron, a contradiction in terms. If we truly are Christians, then we are prophets. Then we truly need to witness to Jesus Christ to whomever we can with the words from our mouths.

The Heidelberg Catechism also speaks about our lives having an evangelistic purpose. The Catechism divides up into three parts: our sin and misery, our deliverance, and our thankfulness. Lord’s Day 32 begins the third part of the Catechism on gratitude. The question is: since we are saved by grace, we must we still do good works? There are four reasons given. One is for us to show our thankfulness to God. Another is so that he may be praised. The third reason has to do with our assurance. And the fourth reason has to do with our neighbours: “that by our godly walk of life we may win our neighbours for Christ.” Living in obedience to God sets us up for evangelistic opportunities. Unbelievers watch and see that we are different from others. That can make them curious. That can make them ask us questions. Questions like, “Why are you different?” Then we can tell them about the Saviour who has redeemed us and who is working in our lives with his Spirit to make us different.

Conclusion

The Reformation produced this vast quantity of confessions. In each instance, the Reformed people behind these documents were seeking to be faithful to the Word of God. I haven’t told you about all the proof-texts and Scriptural support for everything you’ve heard. A lot of it is obviously biblical — at least I hope it is. Certainly we can all agree that the missionary calling of the church is biblical. The Bible calls us to evangelize. Since this is such a strong message in the Bible, we should not be surprised to find it being expressed in various Reformed confessions and catechisms. Now I should add that you will not necessarily find it in all Reformation confessions and catechisms. But definitely in the best ones, and especially in ones that have stood the test of time – ones like the Heidelberg Catechism. In conclusion, one of the most important ways to understand the Reformation is as a missionary event. Because it was a missionary event, many of its creeds and confessions also speak of the evangelistic calling of the church of Christ.

[1] See Williem Heijting, De catechismi en confessies in de Nederlandse reformatie tot 1585 (Nieuwkoop: De Graaf, 1989).

[2] James T. Dennison, Jr., Reformed Confessions of the 16th and 17th Centuries in English Translation, 4 vols. (Grand Rapids: Reformation Heritage Books, 2008-2014).

[3] See my For the Cause of the Son of God: The Missionary Significance of the Belgic Confession (Fellsmere: Reformation Media and Press, 2011) and To Win Our Neighbors for Christ: The Missiology of the Three Forms of Unity (Grand Rapids: Reformation Heritage Books, 2015).

[4] In what follows, I’m using the translation found in vol. 1 of Dennison’s Reformed Confessions of the 16th and 17th Centuries in English Translation, 53-111.

[5] In what follows, I’m quoting from the translation found in vol. 1 of Dennison’s Reformed Confessions, 354-392.

[6] I’m using the translation found in vol. 1 of Dennison, 468-519.

[7] Dennison, vol. 1, 590-642.

[8] Luther and Calvinism, eds. Herman J. Selderhuis, J. Marius J. Lange van Ravenswaay, 195.

[9] Peter Hall (ed.), The Harmony of Protestant Confessions (Edmonton: Still Waters Revival Books, 1992 reprint), 255.

[10] “The Myth of the Swiss Lutherans,” Amy Nelson Burnett, Zwingliana 22 (2005), 48-49.

[11] See Arthur C. Cochrane (ed.), Reformed Confessions of the Sixteenth Century (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2003), 224-301.

[12] Cochrane, Reformed Confessions, 163-184.

[13] Craig’s Catechism (1581) speaks of Christians sharing in Christ’s office as a priest, but not as prophet and king. The Large Emden Catechism asks (QA 135): “Are there no priests any more?” Basically, the LEC’s answer is no.